Using NLP for Materials Science

Published:

At first thought the idea of using natural language processing to discover new materials is counter-intuitive. We think of machine learning as a process that takes in data and learns from important features to make predictions. If those input data are natural language, and the predictions are new materials, then it feels like something very crazy has to happen in-between.

This topic is the subject of my entire PhD, namely answering the question “Can we use NLP, data-science and machine learning to discover new materials?”. With this blog post I will a) explain why we should try, and b) show that we can.

Materials Discovery

Materials are vital in almost every aspect of everday life. From the small, such as computer chips and household appliances, to the large, such as buildings and aircraft. All these applications contain countless materials that have been extensively tested and optimized for both cost and performance.

As the demands of consumers or manufacturing processes change, it is necessary to find new materials that exhibit novel behaviours. This is ultimately the role of materials science research, which aims to synthesise, characterise and optimize new materials. Traditionally, the process of going from a basic chemical compound to its application in a device is extremely slow. It requires extensive trial-and-error and scientific intuition, this is expensive and very inefficient.

Machine Learning for Materials

Instead, what if we could predict the properties of materials before we make them experimentally? That way, we could save the expensive computational and experimental testing only for those candidates that are most promising as useful materials.

This is not a new idea. Scientists have long been considering ways of predicting material properties using basic descriptors. For instance, given a list of chemical elements and their properties, is it possible to predict the properties of the bulk compound (think $H$ and $O$ in $H_2O$)?

It turns out that you can, but only in a limited way. The chemical feature-space consists of all possible elements, in all possible structural configurations, this space is far too large for us to build a suitable predictive model that works in all cases.

This is where machine learning comes in. We know that machine learning algorithms are highly suited to analysing large high-dimensional datasets that are otherwise intractable for humans. So surely, if enough data exist, we could throw all materials data into a complex machine learning algorithm that would spit out new materials. We could then add practical and property-based constraints that make these new materials suited to particular applications.

Of course, the reality is not that simple. It is estimated that the number of possible chemicals is around $10^{100}$, but there are only $10^5$ known materials, currently. Therefore our problem is hugely underdefined, and with such a large feature space, its likely that the ML models models will overfit, or suffer from the curse of dimensionality.

Despite there being several thousand known materials, the biggest limitation for machine learning algorithms in materials science is the lack of annotated datasets. We know that supervised learning uses labelled data to make predictions, and neural networks require tens of thousands of samples in order to learn high-quality models. So what we need are databases of high-quality experimental data, describing materials, their structures and their properties.

The Scientific Literature

The vast majority of existing data on materials are locked away in the journal articles, reviews and theses published in the scientific literature. For hundreds of years, scientists have been publishing experimental results, and around 2.5 million new articles are published annually, and this is growing. Clearly, it is not possible for a materials scientist to read all of the relevant articles, compile all the data and then design a new material. By the time you had compiled enough data for a model to be meaningful, the research would have moved on and you’d have another million articles to analyse.

We need a method for automatically compiling materials data in structured databases from the scientific literature. This way, large databases of high-quality materials data could be used to feed machine learning algorithms that predict properties and new materials. Thereby reducing the “molecule-to-market” timeframe from years to months (or even weeks).

This brings us nicely to natural language processing, as a tool to anaylse scientific documents, extract relevant compounds and identify their properties. However, scientific text is complicated, so how do we create a general pipeline for chemical information extraction?

Documents

Scientific documents are semi-structured. They consist of multiple different data types - text, tables, figures, etc. - and these data are normally read in a semi-linear fashion, since the components are interrelated and may bare reference to each other. Therefore, a general information extraction system for chemical information must be able to handle all the different data types independently and also resolve the interdependencies between them.

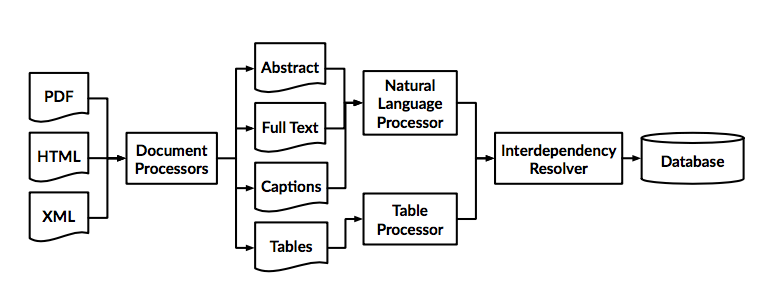

Therefore a general system may look something like this:

We take as input scientific documents in HTML, XML, PDF or other formats, and break them down into their constituent elements.

Text gets processed as individual work tokens by applying conventional NLP techniques, tokenisation, stemming, lemmatisation, stop-word removal, Part-Of-Speech tagging etc. in order to remove noise and highlight the important content.

Tables must be processed completely differently since they are semi-structured in a row-column fashion.

Figures are even more complex, and computer vision techniques must be used in order to retrieve relevant data.

These are all very complex problems.

Named Entities

Scientific documents are also full of important named entities - chemical formulae, labels, aparatus, measurement techniques etc. - which are made even more complicated by the use of domain-specific abbreviations and terminology. For instance, if undefined, the abbreviation DFT means something very different to a computational chemist than it does for a mathematician. Identifying and resolving these kinds of issues (a word-sense disambiguation task) is highly important.

Chemical naming conventions also vary wildly between domains, a single chemical compound could be identified by a formula, IUPAC code, common name, brand name, SMILES string and more. As such, Chemical Named Entitiy Recognition (CNER) is a vital part of the NLP pipeline.

Relationship Extraction

If named entities can be identified accurately, then the main goal of our chemical information extraction system is to extract chemical relationships. These are typically the relationships linking chemical compounds to their phyiscal properties. For instance, we may wish to extract important properties, such as the melting point, of all known materials. This forms a relationship that links compounds, values, units and ancillary properties like the measurmeent technique used or experimental conditions.

Interdependency Resolution

But as we said before, the entities are separated across multiple different data types. We may find a partial relationship in a sentence of the document e.g. “The melting point of compound 1 is 100 K” but it turns out that Compound 1 was defined in a table somewhere:

| Formula | Label |

|---|---|

| C64H8 | 1 |

then, to make matters worse, the structure of Compound 1 is given elsewhere in a crystal structure database. To gain a full picture, we need to resolve these interdependencies.

Overall, we see that chemical information extraction is a very complex task. However, the development of tools, such as ChemDataExtractor make the process much more manageable, by providing a complete toolkit for general chemical relationship extraction.

What’s the point?

So we can extract some properties and chemicals from documents, why is that important?

Well, consider that we can extract all relevant chemicals and their properties from all relevant documents. We effectively auto-generate a vast database of labelled chemical data, upon which our aforementioned machine learning algorithms can be applied. This builds highly accurate predictive models of materials, that ultimately help us to discover new ones.

Does it work?

Yes it does!

Using these kinds of approaches, researchers have demonstrated it possible to build vast databases of magnetic materials, photovoltaics and battery materials. These have also been shown to produce accurate predictive models and even discover new materials!.

Conclusions

While it definitely is counter-intuitive to use NLP for materials discovery, the utility of NLP in the scientific domain should not be underestimated. Hopefully this blog has given some insight into why it’s important.

Feel free to contact me if you’re interesting in applying these techniques to your domain of interest.

Cheers,

Callum